|

|

by Damir Salkovic The girl turns round and smiles, a bright white smile in a

freckled, suntanned face, more dazzling than the cloudless day that bears down

upon the wasteland. She’s wearing a haphazard assortment of army cap and faded

fatigues and a tie-dyed shirt, washed so often the colors are running together.

Under the cap, her strawberry-blonde hair is tied up in a bun, but she brushes

long, capable-looking fingers though the few escaping strands, mouths something

unintelligible at the camera. We’re here, or maybe come here. The lens zooms in clumsily

and her face goes out of focus for a moment, a shadowy blur. By the time it’s

brought back into relief, only her eyes are visible, her nose, and that

blinding smile: a moment trapped on an old memory wafer, nothing but colorful

pixels and automated routines and below them a game of zeros and ones, an

infinity of them, already degrading into nothingness. But the smile stays with you, etched into your

consciousness. Memories swirl out,the

same giddy flutter in your chest you had back then, the same satisfied warmth

in your empty belly. You smell the hot dust of the Apocalypse Trail, feel the heady mix of fresh hope and old desperation.

For a moment only, the sun is hot on your face, all the weary miles behind you

fall away, all the impossible miles ahead mean

nothing. As the clip loops once more, as she spins to look at you and smiles

that perfect smile, you know your journey is already at an end. You have

arrived. - - Kyle flailed in null-space, his brain tugged apart by opposing

inputs: the cornflower-blue of the desert, the soft memfoam

of the immersion chair. It could not have lasted longer than a single flash of

synapses, but it felt like forever, an unpleasant, vertiginous sensation, like

falling into an abyss in his head. Then he was back in the studio, back in Realtime. The image was just an image, flat and

two-dimensional, a jarring crackle in his optic nerves. He played the clip

backwards, millisecond at a time, and the girl’s movements were reversed. She

was turning to hide her face from him, exiting the frame. Kyle went over the loop several times, pausing, zooming, looking for inconsistencies in the metadata, telltale traces

of forgery. There was nothing. It was the same girl. Impossible,

but no less true for it. Somewhere miles away, his fingers moved across an invisible

control pad. The vision cut out, replaced by the greenish-blue recalibration

screen. Kyle’s senses cleared of the desert. His headgear clicked and whirred,

retracting on its waldo.

Sweat matted his hair, the metallic taste of neural comedown bitter in his

mouth. The screen beeped, warning him that he had clocked out and that his pay

would be docked. On either side of him, other bodies lay behind plexiglass partitions, twitching and stretching in their synesthetic rigs, headgears encasing their faces like alien

armor. Kyle ran background on the file, waited for the search

engine to chew through terabytes of data. The studio collected material through

myriad channels, from discarded surveillance tapes to unclaimed family holovids to random clips floating around the grid. A

halfhearted attempt to sort and log the entries had been made in the past, but

the sheer volume had quickly overwhelmed the paltry resources dedicated to the

task, and the parent company now found it cheaper to settle copyright

infringement claims as they arose. Kyle’s search terminated in a dead end, as

his corporate clearance did not extend into Records. Even if it did, his

chances of learning more about the mystery clip’s origin were slightly lower

than finding the needle in the proverbial haystack, only blindfolded and with

one arm tied behind one’s back. In his six years with TransCore,

Kyle had churned through millions of vids, thousands

of hours of recording. Snippets of other people’s lives, old photographs, archived travel and nature documentaries – all filtered and

edited and blended in the Augmented Reality Interface’s AI processors,

extracted and pureed into paywalled mass-market

broadcasts. Dismissed as synesthetic garbage by the

purists, eagerly consumed by the public, the resulting immersive experience

packages were beamed into home consoles and simulated vacation centers at

staggering rates, stimulation-hungry brain cortices always clamoring for more. But software, no matter how advanced, could only do so much.

The input, the raw, regurgitated data, came from human processors, like Kyle.

For every half-hour spent climbing the long-melted glaciers in the Alps, or

surfing on a Micronesian beach that now lay at the bottom of the sea, hundreds

of unconnected impressions had to be reviewed, rewound, manually tagged: the

properly timed release of artificial pheromones, the chemically induced sense

of vertigo. Kyle was a script runner for TransCore

and sometimes freelanced on the weekends for immersion indies.

His credit was solid, his skills unremarkable, but in demand. He had a balcony

unit in a corporate highrise, a taste for creature

comforts, and little ambition. Life rolled along on a greased track, every day

exactly like the next – a cocktail after work, a vista of the ethereal poisoned

sunset suspended over the brutal lines of the housing blocks, then bed and the

sweet oblivion of sleep. He wanted for nothing, existed entirely for the

present, and let the past be the past. Except the past did not seem to be done

with him. Kyle tapped the

armrest absently, wondering how the clip had made its way into his queue. He

couldn’t accept that this was an accident, some random collision of chance

events. The universe giving him the finger, or fate trying to

get his attention. It was one thing to reject superstition, another to wilfully close one’s eyes to what was happening around him. He reached for the headgear and it responded to his

movement, sliding down to clamp over his face. Light replaced the calibration

screen, and from it the desert appeared, the sun eternally in its place, the

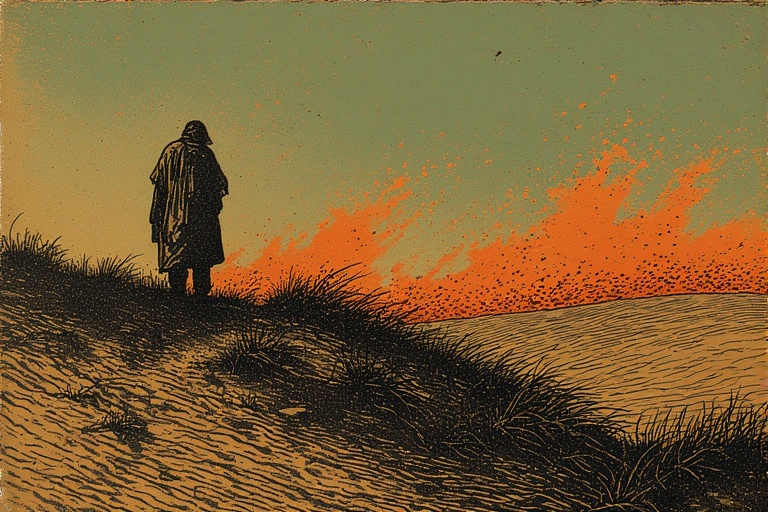

sand and slag burning under his soles as he trundled on, remembering. - - In the first year of the great fires, he had followed the

exodus north from the Gold Coast, hungry and afraid and thinking only of

survival. He wasn’t Kyle yet, but had another name, one that would later be

swallowed by the conflagration of the communes, along with everything else. The

river of dispossessed, terrified humanity passed through collapsed cities,

picking up rivulets, building to an unstoppable torrent. The Of his stay in the city, he retained short, ugly images: gray ocean washing up trash on the oil-slick beaches, gouts

of smoke blackening the sky, the reek of burning and ashes everywhere. But it

was home of a sort, and Kyle made connections, people who thought like him, who

wanted to build a better world from the ruins of corporate greed. He met Marnie on a night when the

commune was throwing a block party, food and booze options limited, but drugs

flowing freely. A skinny blonde girl had appeared on the makeshift stage and

proceeded to spin a holoprojection of roaring,

flame-breathing dragons, of cavorting naked faerfolk

with diaphanous wings, of armored knights charging across phantasmal landscapes

on hulking six-legged steeds. Strung out on a particularly potent concoction

brewed by the commune’s resident shaman, Kyle had cried, then laughed, then lay

on his back, stupefied, letting the visuals bombard his brain. She’s the best I’ve experienced, one of

the other artists had confided in him. A neural jockey from some town up in the mountains. Make you feel on top of the world, or shit

in your pants, or hide under your bed, man. She plays your gray matter like

piano keys. It was a new fad on the Gold Coast, Marnie

explained to him some days later, between bouts of breathless lovemaking.

Synaptic interfaces that blended reality and dreams, transformed the resulting

sensory mess into myoelectric impulses that could be

‘cast just like any other signal. Cheap immersion goggles and earbuds for the everyman, expensive wetware augments for

the rich: the point was that everyone could do it, tune in and ride the waves

of someone else’s imagination. Some pre-deregulation techbros

had invented it as an inside joke, but the sensation-starved masses had

embraced it full throttle, the ultimate drug of the proletariat. The raw

material was the neural equivalent of white noise, as like as not to burn out

your sensory cortex for a few days. In more extreme cases, the damage could be

permanent, leaving you a vegetable. It took a master jockey to figure out just

the right balance of input and designer chemicals to launch you to the precipitous brink of experience, imbue you with feelings

you’d never experienced before, see the world through new eyes. Marnie had the touch, could mix and swipe

right along the best of them. Night after sleepless night, she continued to

experiment with form and frequency, building up a portfolio which she stored on

microcards. She had not had to work her neuralink magic on Kyle: he’d been smitten from the moment

he lay eyes on her, lost in her gaze, then inside her

head, in her vibrant, glorious mind, falling forever. For a time, life seemed

to be looking up. The commune and its vibrant art scene provided a sense of

security neither of them had felt before. They had carved out a place for

themselves and hoped to move onto bigger and better things. But the idyll couldn’t last. The fires raged on, the food

ran out. A nascent avertical farm was blighted by a

virus left over from the Silent War, another one torched in a drone raid,

allegedly by accident. People went missing from the ravaged streets, never to

be seen again. Corporate-funded terrorist groups waged a proxy war for the

city’s shelled-out industrial district. Their new world was dying before it had

taken its first breath. Marnie pawned her splicer module for twelve

cans of baked beans, her interface web for water purification pills. “It’s

okay,” she said when Kyle objected. “The big companies give you your own gear

when you sign up for them. Mine was crap anyway. Just stuff I strung together.” She was confident that she could sell her work, and Kyle had

to agree: her sequences were better than anything he’d experienced before. It

didn’t take a genius to predict the coming synesthetic

boom. There was a future waiting for her outside the western wasteland and the

cordoned zones – a job offer, corporate housing, credit that bought you

whatever you wanted off the shelves at the store. All of it could be hers.

“Ours,” she would say, smiling at him in the blackout dark of their hiding hole. “You and me, we’re joined at the hip now, picaro. You’d

better not forget that.” - - Marnie needed tranks.

Lots of them. Mixers skated along the razor edge of

reality, gambled with their brain biochemistry, took excursions into uncharted

waters. There were dragons in those waters, chimeras that gnashed monstrous

teeth and flapped their wings, filling her nights with screaming nightmares.

Kyle held her when she sobbed, restrained her when she ranted and bit and tried

to scratch his eyes out, hallucinating horrors. Kept the blinds down when her

eyes burned from the sunlight. Meds ran scarce. Corporate militias were

advancing, and a new and terrible order was establishing itself in the

territories outside transnational control. Stories proliferated of rapes and

mass graves, of internment camps for undesirables being established by various Dominionist groups. Time had come to move on. Kyle had connections that could fix their way out, but the

window was narrowing. False idents would see them

across the spreading desert, east across the stricken heartlands, eventually

into the vast conurbation that took up most of the Eastern Seaboard. Corporate-controlled, but with plenty of niches to slip into and

disappear. Marnie had other ideas. The

Pan-Pacific called out to her, or the controlled anarchy of the new pirate statelets in the After she’d fallen asleep, Kyle lay awake in the darkness,

listening to distant gunfire. Things had moved past words with them. Angry as

he was with her, he realized that his feelings had a deeper root: he resented

her talent, her ability to take charge of her future, reshape her world into

whatever she wanted. She didn’t need him, but he would be lost without her. The

thought gnawed at him as he sweated on the lumpy mattress. By morning, he knew

he’d never be able to change her mind. There was only one thing left for him to

do. - - He negotiated passage through the corpsec

barricades with a fixer who ran drugs for the Patriot Banner. Snuck out a few days later while Marnie

was playing her set at the Dune Club, past the barbed wire circling the

commune, past dirty, burly sentries in mismatched uniforms with last night’s

liquor on their breath and murder in their eyes. His journey east was

long and dangerous– hunger and thirst and cold, armed marauders prowling the

emptiness. He was almost stabbed in a fishing settlement on By the time he reached the outer edge of the megasprawl, the fall of the communes was on all the ‘casts,

the corporates denying responsibility, the bleeding

hearts expressing indignation, stock cars full of dark faces dispatched to the

camps down south. Kyle found the bad news easy to ignore. The synesthetic mixes on Marnie’s microcards earned him a foot in the door with TransCore’s nascent immersive entertainment division, and

Kyle was a quick learner. He meted the material out for months, then finagled his way into a position with no creative

responsibility. Much as he expected, it was easy to let the sprawl open up and

swallow him, the acid rains wash away the last traces of his guilt and regret.

Gradually the Gold Coast receded to a memory. Perhaps less

than that. Perhaps it was just a fragment of a synesthetic

trip he’d once taken, a piece of someone else’s dream, already fading in his

mind. - - There were consequences to removing or copying raw material.

Kyle was well aware of the studio’s policy, the terms of his non-compete. But

he’d gotten away with it enough times, and he had his methods. These soft

corporate boys and their rulebooks didn’t stand a chance against a slum-raised picaro, cheating

and smuggling and stealing almost before he could walk. In the dimness of his apartment unit, a soothing classical

piece on his stereo, he pasted the interface trodes

to his forehead and temples. Set a two-minute alarm on the trigger switch and

shoved the transdermal into the crook of his elbow,

his eyes closed, every nerve tingling with anticipation. The transition was

smooth and faster than anticipated, his mind liquefying, expanding into

another’s simulated memory. A dry, hot breeze slapping his

clothes against his body, grit crunching under his feet. Her feet. He was

no great talent, just a paint-by-the-numbers drone following in the footsteps

of a master. But the work was passable, and the sensations, albeit counterfeit,

felt real. Kyle relaxed into the mix, let the walls dissolve around him,

replaced by the enormity of the desert. Maybe he had it all wrong. Maybe this gray reality was a

dream, the past six years an illusion. Maybe his body

was lying in a ditch, a bullet with a biblical inscription lodged in the back

of his skull, his dying brain replaying a fantasy sequence as consciousness

faded. Maybe that’s why it all felt so empty, so thin and tasteless, like a bad

trip mixed by an inept hand. Only when the illusion began to lose dimensionality, the

images turning into flat monochromes, coming apart at the seams, did his

earlier suspicions rear up again, followed by a sickening jolt of fear. He

groped for the switch, but the shattered vision persisted. Heaven

and earth running together, wearing thin in the center, revealing a hidden

subroutine spinning underneath. An assassin virus, crafted to resemble

nightmarish horrors, relentless teeth and gaping gullet. Eating

through the synesthetic barrier, eating into his

mind. There were no coincidences, he realized with the last of his

thoughts, only cause and effect. Then a black wave swirled over him, and this

too was gone. - - She

smiles at him from the frame, the barren plains rolling all the way to the

horizon. If he focuses enough, if he gets close enough to see the pupils of her

eyes, he might see what’s reflected inside them. Maybe his

own face, which he can no longer remember. But the girl turns around and

walks away, and he stays where he is, already forgetting why this moment is

significant, forgetting why he’s there in the first place. Dust sifts into her

footsteps, covering them up, as her figure recedes into the distance. Sand

burns on and on under the cornflower sky.

Damir Salkovic is the author of In Lost Country And Other Divergences, a collection, and Collapse Years, a novel. He lives in Arlington, Virginia. |