|

|

by Andrew Aulino

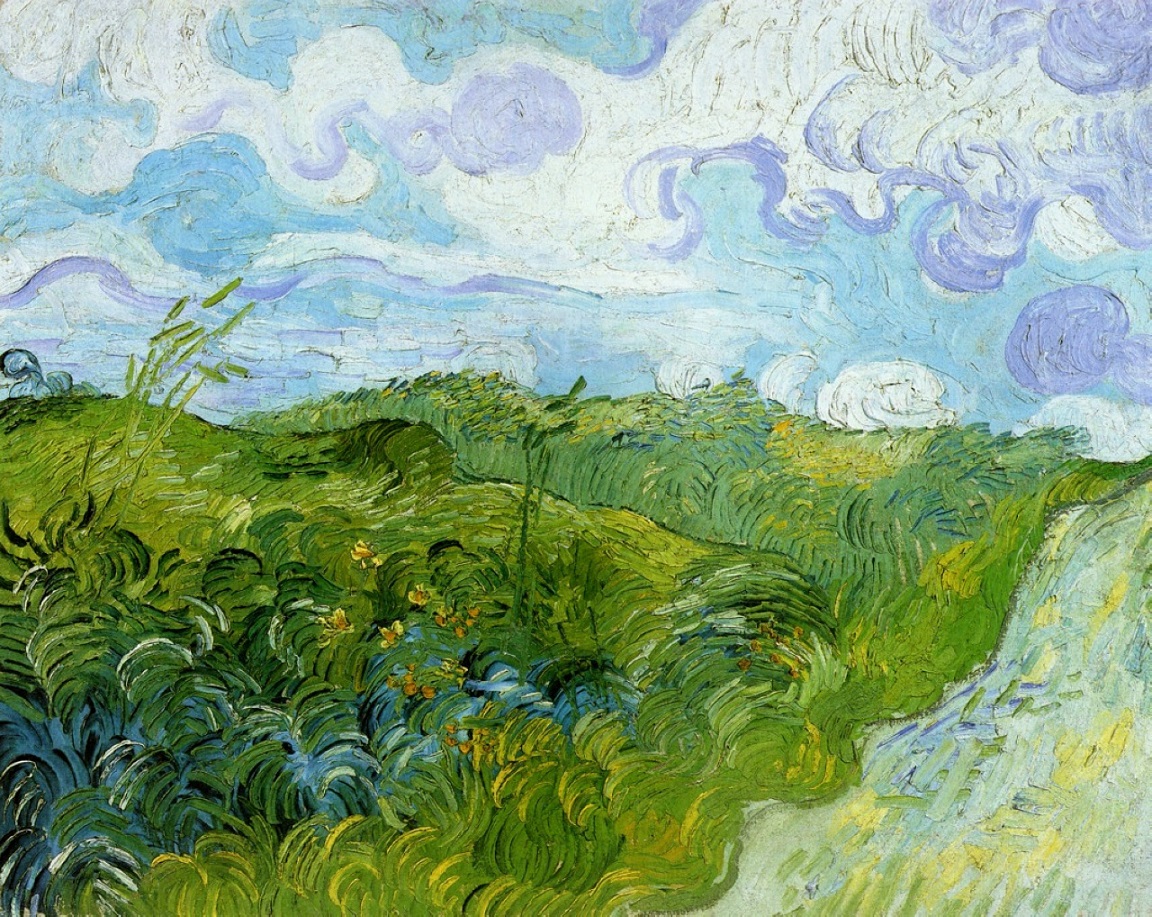

Green wheat fields, Vincent Van Gogh There

was a day that she left the meadow for the forest, their untended property's

edge. It rose straight up from the low curves. A

thin hard tree stood at the edge of the forest, cleft in two branches it held up like

two Statue of Liberty arms. From overlapping, scaly leaves it sprouted enormous

gourds. Sleep by the shade. The voice

was soothing and light, a voice for motherhood. It was very soft. Though she

preferred standing out here, she stretched up to look

at the gourds' bulges. Maybe they weren't hard at all. It was easy to image

soft slits open in them, small bodies pushing out and making long turns towards the grass as if

they wanted to find the longest way to the ground She started into the overgrowth and found it

so dense her vision didn't reach more than a meter or two. No plant had a

visible twin, only another blossom; wet stringy vines; the weeds’ leaves had ingenious shapes that would

have slid from a jigsaw. Buds crept on tethers of the roots. She startled

insects of bark that opened scratching wings. Every living thing pushed in

close. She twisted her neck aside to avoid the huge influorescences. Each one had a vivid color

despite the dark. The canopy's crush had

thinned the sunlight; branches rained. Water, slime, nectar. A globe with the

tang of carbon slipped into her eyelashes. Then another, into her eye; a satin

stroke was moving across her face that smelt of fossil fuels. When it moved away

seven violet petals burst out toward her. It had left a line of those kerosene

droplets across her cheek. A half kilometer in

she was cold and getting steadily wetter from the plants and an inexplicable

sweat, though the temperature was pleasant. How silent; her breath was

louder than the wind that didn't make the leaves rustle. Transparent ripples

crossed the ground, between trees on low branches. Reptiles camouflaged

with quiet and stillness; she saw what looked like a smoothly

brown trunk turn a pair of yellow eyes. You could be prey here. The same voice. Calm, serious. She

walked another kilometer and was surprised to find a bright fruit tree. Citrons, maybe. Thin sunlight played with their color but

the smell was lovely—floral and sugary, but a little acidic; her prodding

finger found their skin thin and soft, like apricot. To eat that smell; a flesh to drink. Why

was she not hungry herself? Her mouth

turned sticky. Her sweat, too. Those fruit were

sickening. It was as though she didn't have a stomach. It hadn't growled at the

joyful fruit-smell, nor turned over now. A nausea seeped through her, not from the guts. It leaked in

like an abscess, a nausea of muscles and skin; her

heart felt huge, it beat furiously, with a gush of sweat. A hypoglycemic's weakness. She shook at the

thought of vomiting, if she was going to. She would burst like one of those

fruit gone overripe, guts dumping themselves from her abdomen and thighs. It

would happen, staying there. She knew, also, that she knew the way back, knew

that she knew the straight line she’d followed; she turned and began to follow

it back through the green smear. Her lips shaped a frantic whisper, the motion

of prayer without praying, not shaping words she knew; all her voices were

gone. A vestigial tic of fear. She began to move faster, raised her knees

so she could almost run over the layered

ground. The run of a horse who never got the hang of being a horse, bad at the

species. It moved her faster faster than she thought. She didn’t see a thing she

passed from the shade of the gourds with a cutting joy in the flesh,where the sickness had been. On the meadow, she let her elbows and knees come loose and

collapsed. She lay a long time, looking without any focus at the distance,

trying to drag out the feeling of relief, the pleasure of sore muscles clinging

to the edge of wakefulness. Cells swelled and stretched for the sun's heat;

open-eyed sleep. By

the end of her slow walk back to house she felt

replenished. She was sure she'd return so exhausted that the bedroom would feel

impossibly distant, and she would spend the rest of the day sleeping on the

couch. Something in the light and heat had done it. Standing outside after leaving the forest had

been like going

through the full course of an illness and recovery in a few hours. Only

her skin bothered her. A tacky splotch like pine tar on her temple reminded her

of the life that had been all around her. Everything there seemed to prod or

pinch her, and in her memory all that damp flora had

seemed to desire it, to examine the new foreign growth moving among them. Just

the way a cat showed hostility and fear in a glance, it was the way their fronds

had sagged and bobbed beside her head. She had been so wet. Wet from the touching of strangers she couldn't push off. It took three mornings of dedicated scrubbing

to feel cleaned completely of the stuff; she would, she thought, scrub until it

rolled off with the dead layer of skin. Even then, an accidental brushing of

the hand against its remnant brought her up against the thought that she'd been

wet by the touch of so many strangers. She was still wet, and didn't want to

look at herself; it seemed that she'd find fingerprints everywhere, long

smudges from the hands that couldn't help their own curiosity and reached for her.

There were none there, but her hair and parts of her clothing, the shoulders

especially, were almost soaked through. A scratch ran the length of her cheek,

bright pink, like an infection. She

wasn't going back there. Why had she done it in the first place? She has grown up in that house already

accustomed to the idea that this was her place, her family's place, and the

acres they paid to have tended stopped at that woods. These were bare, dull

facts. To go in would have meant being "out of place," as her parents had put

it. Out of place. It seemed imposible,

but the yard had never interested her. The land they owned was nicely manicured;

but it was no more than nice, the simple prettiness was worth a look, and

forgettable. The

fascination of those strange gourds had brought her in. What she’d wanted was

to see, but if she ever felt like looking again she could find them on the edge

of the trees. She could look without

going in. She

had another reminder in the scratch, which she must have gotten from the slap

of a pushed-off-branch when she'd gone in preoccupied with the fruit. That, the

scratch, reminded her constantly for the week it took to heal. It had swollen

up a little now, all pink. That irritating stickiness of the fir-sap had moved

into the it.

Within a day the same feeling had spread everywhere under her face. It tingled, or crawled in

place, suddenly motile. When it appeared, she spent whole minutes scratching at

it. Finally it came down to the bottom of her neck. But it

didn't have a place. Even when the skin

was smooth again, the tacky spot washed away, even a straying hair would tickle

the spot, and she scratched again. Sting

and itch abated when the cut faded, but after the skin’s original smoothness

returned, the rest was somehow not the same. Her body demanded attention it had

never wanted before. Hungers for sun set into her. Every workday she found a way to go stand out

of sight, looked up. She spent her lunch hour sitting outside

alone, with eyes shaded, getting warmer.

Otherwise her muscles would feel turned to exhausted pulp, as if she needed

the heat to keep them firm and didn't tense or flex according to her own needs.

She felt the same misty sweat and dizziness from the darkest part of the woods. That light seemed to guide them. When someone whose desk

was on the window quit, she asked to move in. "Wouldn't

you rather have the cubicle?" the manager asked. "You have more

privacy there, I know it isn't much, but it's something." "No,

I don't mind it. It's okay that it's in the open like that, I'll be fine." The

manager tilted her head. Was her tightened mouth skeptical or concerned? Both? "Are you okay?" She

considered telling the woman that she liked the open space and wanted the

warmth of the sealed window, but it would have been a bad lie. Though the walls

of the cubicle were beginning to feel tight, she’d have less privacy—she’d even

told her manager on one of her first days that she didn’t mind the small space

because "it was more private." "There's

nobody bothering—I'm not having any conflicts or anything." "I

see. Well, if you want it, be my guest. Brian was all cleaned out yesterday so

go ahead and move when you’re ready. You're sure you're

ok, though?" Her demeanor was pleasant; her words grasped. Once

she’d finished moving desks, she felt pleasant and quiet. Work required a

couple of reflex actions that came easily; part of the job was reviewing other

peoples’ materials. She no longer thought much of anything. Her

focus attenuated until it was nearly passive; despite the minimal place she’d kept

for looking out she found that her movements through the changes of the day

remained largely the same. The

sun cravings weren’t a worry. She was

used to going outside when the three or four other smokers did, it was easy to

set a routine of going outdoors around that. If anyone’s eyes met hers as she

made her way, she murmured “smoke break” and smiled tightly. The light in the window was enough to keep

away the ill-feeling. Between her trips to the southerly side of the building’s

fence she looked forward to the sun, drifted into daydreaming fondly about it.

Sunlight had its own scent, dry and starchy, and it caught itself

into the weave of peoples’

clothes and came in with the fresh air when someone arrived or returned. The

only thing that broke through the haze was realizing that a change did seem to

have happened throughout her. Yes, the cravings now seemed to come from her and

make her newfound love of the sun zealous, her body really had somehow shifted.

Her appearance hadn’t changed but she felt that underneath the skin, its

orientation shifted. It was as though that need for warmth and light was a

common point inside her flesh, broken and shared with herself. What nonsense. How could you share anything

with yourself. How could you do anything but? Besides,

it might not have been a change at all, but the result of the obvious

difference inside her. She didn’t have any symptoms. Clearly it was nothing. If

it came to mind, she tried to think of leaning against the fence to feel the

heated diamond-shapes of the chain-link pressing through cotton and into her

shoulders, and turning her face. The

peaceful time didn’t last.The few weeks of lingering in sunlight, and savoring

its soothing haze, and daydreaming of standing by the fence had suddenly passed

when she noticed the mass. One morning, giving herself a quick inspection in

the mirror she saw a swelling at the bottom of her throat just below the

voice-box. It didnt’ seem unfamiliar; she seemed to remember some small blemish

there the previous week or so. She’d

forgotten it as soon as another lingering daydream set in. It was strange for

it to be there, and to have grown, it was now the size

of a large pimple, but she pushed it aside. The idea of some other interruption

was enough; the lymph and pits inside a boil fit too well among the bleeding

plants and large insects she had just started forgetting. Let it go. It would go

away by itself by the end of the day. When

she examined it that evening, it had already grown. it was softened as

her . The skin she pressed gave way but though it, between her thumb and

forefinger something harder and more circular was there; it would have felt

like a grape if she could hold it. It slipped a little. A

cyst. A lttle abcess. It would come to a head

and open itself under hot compresses., All of it was

painless. When she pinched it, it didn't feel pinched at all. It didn't feel

like it had been a part of her; it had only grown there inside her, contained

by her own skin. It was a natural thing. Not that many years ago she would have

been mortified that it had budded on her at all, and so visibly. Now she wasn't

worried at all. Her unconcern did not occur to her; instead, she remembered

scrubbing away at the spot of sap and wondered why she'd been doing it. That

felt unlike her, now. The

cyst—the abscess—the mass—whatever it was, she hadn't found a word for it and

did not want to—was swelling on its own schedule. The length of that schedule

was impossible to tell; the change

between days had recessed in favor of the placement of the light.When she could

no longer hid her, it filled the whole of her hand. Left to the open her would

mean subjecting herself to scrutinizing questions, coworkers who would lean in

close, fascinated and reciting opinions and advice. Her body stiffened thinking

of three or four faces leaning it to scrutinize and point at the mass, the

nagging warmth of their breathing rhythm while they spoke. Someone would want

to touch. That would be easy to pass through patiently, but she worried that

one or two of them had been seeing more—the move to the window, the 'smoke

breaks'—and stay persistent. It was impossible to tell how long it took prying

kinds of people to get accustomed enough to seeing it there that they got bored

with it and moved on to a new interest that they could stretch out longer. A

doctor would be unthinkable. From the minute she let it be shown, eyes and

fingers and mouths would cover her; the more who

looked, the more that would be close enough for their breath like to would

condense on her. Their fingers would poke the mass, touch her neck and wrist.

They would lean their heads down towards her speak to her in the same softened, enticing

voices they'd use taking someone to bed; in time, she would be as soaked and

streaked, have layers of fingerprints and the oil of their skin covering her.

Even a hint would crowd others as thickly in around her as the flowers and

tenders she'd walked through, whatever pertained to her would be the slow

tangling of her body from a group who desires not just to feel but to take

something from her that she would only discover as they laid themselves onto

her. Whatever

was amassing at her throat had its covering of skin, but the skin had no

covering. She would have to wrap herself around that, chin towards the chest,

forehead her knees, wrapped in her arms. Someone would take it. In the world of coworkers, paperwork, doctors

and orderlies she and her body were the new inhabitants; someone would break

her open and take her new center. She put both hands over it. This is mine. She

did not know whether to gouge it out with scissors or ball herself around it. With the body left to attend itself, she

was in prolonged fright. When she had

only hungered for the sun, the world felt benignly veiled. Every color was saturated now,

and the evening sunlight felt insufficently to a faster-seeming day. A bird's hunting jab would find her in her

sleep. The only thing was to keep away completely; she had left early that day,

and called in sick for the following day before four. Finally,

after an afternoon spent stiffly pacing the ground floor of the house , she

dreamed that hands like a rancher's broke the cyst open and let seeds and juice

run down his big hands. He passed it to others, who passed it among themselves

and drank. When she woke up the sun filled the room; its light having

strengthened and rested her at once, but she was bereft before she was fully

conscious. An uneven slit had opened the center of the cyst. It was empty; thin

liquid whose smell reminded her of gasoline bubbled in the outward gouge. It

was on her cheek; on her pillow and floorboards. Following the hallway to the

end she saw dabs and smears of the nectar, just a few. The smell of the nectar

was the same as the woods, the smell of gasoline and peach. She remembered how

the long scratch had swelled; rocky-looking flowers, the spiked-leaved bushes

and the vivid flower that had drawn along her cheek. The

constantly-raining treetops. Just one had scraped or dripped its pollens

into her face, only seen its fruit, also made of her flesh. Her

neck ran a light brown until the following morning, when it closed under a few

hairs’ breadths’ of a seam. Otherwise the year’s end was calm and

regular. The following week she’d returned to her desk ,

her window and her daydreams. Nobody asked where she’d been. She spent the

summer and fall with them in that quiet way.

She appreciated the winter. Softer sun and shorter days didn’t leave her

ill. It felt better to be the house was she thought. on the other sides

of the walls were her own rooms. Everything

she had was there and she was glad to lead a solitary

life. She was grateful to her parents for leaving her the home. Two or three

days could by without drawing her attention to the noise. It

was not until then that she realized she rarely thought of what had happened;

the process was through in no more than six week. She had no more interest in

recalling the details memory than an especially difficult illness. When she did remember what she eventually decided

to call the incident, it was the two strange gourds, or a large insect.

Anything else kept the mixture of strangenesss and silliness that were

embarassng to deliberately put them together.

That she’d been sharing the nutrients of the sun with some part of

herself had been true, too, though, unless one of those appearances from

the forest did make its way to her and flicker, as it seemed to, on the backs

of her eyes. The

plant that she could only remember by the odor and color had brushed her, as

much an accident of circumstance and biology as anything that is birthed and

mates. A collision and

scattering. She didn’t know what

her “children” look like, but imagined they resembled her and have passed

themselves back to the ground with a drip from the eye or wet cough. But just

as likely the stood in a marsh , opening seven petals

in the middle of spined. None of them

had a name. She couldn't compare their leaving to an adoption, When they left her body, they felt likes abstract

curiosities no different than lives she might have but did not lead. Once,

though, a light rail stopped suddenly and brought her head up to see a couple

opposite. They looked like close relatives, each face resembled hers as much

had each parent’s had. Both man and woman were close to her own age. She watched them cross her and stepped down

the street; they kept cloe together together, their gait one of siblings, not

lovers. They left the car smelling faintly of fossil fuels as if it perfumed

their hair. Now

that the season has come again, she is lying on grass already grown long. As

the year had opened itself up, her desire for the bare sun has grown sharper than the

previous year, its own need and pleasure like sleep and thirst. With its familiarity, a space opened up in

mind and shed wondered openly why she had taken up the whim to walk out towards

the forest, and an image of the twin fruit held up like scales would join it, a

different disruption for a different year that drew her back towards it. She returned to the edge of the property with

the absent manner of someone finishing an errand. No

longer indifferent to her surroundings, she doesn't imagine herself leaving

house or grounds. It is as if one violet

petal placed itself where the flesh was scraped from her; its more resilent

cells sealed every cut quickly. It is hers, too, but not over, a

she-but-not. This wider life is grasping

in her cells; perhaps each one acts like a hook, pulling her back and keeping

her near land. She

lies late into the afternoon. A dense lump of cells mass in

her throat, a hard half-circle of Adam's apple, the clutch of her children.

She palms it softly. All her cells breathe an atomized sky. It feels good.

Andrew Aulino lives and works in California's Central Valley and makes occasional visits to Kentucky. |